Labor Resistance and Economic Inequality in Industrial America (1865–1900)

Industrial Growth and the Rise of Wage Labor

After the Civil War, the United States experienced rapid industrial growth that transformed the economy and how people worked. By the late 19th century, the U.S. had become the world’s leading industrial nation. Railroads sprawled across the continent, steel mills and oil refineries multiplied, and new inventions (like the telephone and electric light) boosted productivity. American cities swelled with factories and workers: for example, Chicago grew from about 110,000 people in 1860 to over 2 million by 1900 as industries like steel and meatpacking expanded there. This fast growth was fueled by abundant natural resources (coal, iron, oil), government support for business, and a growing labor force of immigrants and rural migrants.

One major change was the rise of wage labor. Wage labor means working for an employer for a set wage, rather than being self-employed on a farm or in a small shop. Before the Civil War, many Americans had been independent farmers or craftspeople. After the war, more people became employees in someone else’s business. By 1880, for the first time in U.S. history, over half of the workforce held non-farming jobs. By 1890, about two-thirds of Americans worked for wages (in factories, mills, railroads, etc.) instead of farming or running their own small business. Control of agriculture in the hands of fewer and fewer farmers who owned all the good farm land pushed many farmers to cities to find work. This shift to wage labor meant that millions of people now depended on industrial jobs to survive. While industrialization made the nation richer overall, it often left individual workers with less independence and more vulnerability. The fortunes of workers rose and fell with the economy, and they had little control

Harsh Working Conditions for Laborers

Industrial workers in the late 19th century often faced very harsh working conditions. Unlike today, there were almost no laws at the time to protect workers’ safety, health, or income. Some of the major problems included:

-

Extremely long hours – Factory employees commonly worked 60 or more hours per week, often 12 hours a day, 6 days a week. They had very few breaks and no paid overtime.

-

Low wages – Pay was often so low that it barely kept a family alive. Many working-class families remained in poverty despite everyone in the household (including women and children) working.

-

Dangerous conditions – Workplaces like mines, railroads, and mills were filled with hazards. The United States had the highest rate of industrial injuries in the world at that time. On average, over 35,000 workers died each year in work accidents (such as machinery accidents or mining disasters), and many more were injured.

-

No safety net – If a worker was hurt on the job or fell ill, there was no insurance or compensation. There were no pensions, health benefits, or unemployment benefits. An injured worker could easily lose his job and have no income.

These conditions meant that working people led hard lives. They toiled long hours for meager pay and could be hurt or fired at any time. During economic downturns (like the severe depressions in the 1870s and 1890s), many workers lost their jobs, and unemployment was high. The government did not provide when they could not work. Thus, job insecurity was a constant worry. Families often needed women and children to work as well, just to make enough money, leading to child labor in mills and mines. Work environments were crowded, dirty, and unsafe, whether it was a sweatshop sewing factory or a coal mine. All of these difficulties contributed to mounting anger and frustration among the working class. Increasingly, workers began to organize and push back against these conditions, giving rise to a growing labor movement.

“Robber Barons” and Monopolies

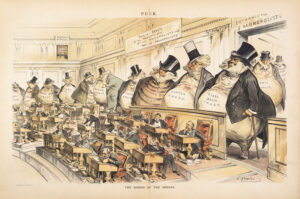

An 1889 political cartoon, “The Bosses of the Senate,” portrays huge money bags (representing wealthy monopolists) looming over the U.S. Senate. During this Gilded Age of industrialization, a small number of very rich and powerful industrialists came to dominate the economy. These men – sometimes praised as “Captains of Industry” and other times criticized as “Robber Barons” – built business empires that crushed competition and amassed great fortunes. John D. Rockefeller monopolized oil refining with his Standard Oil Trust, which by the late 1880s controlled about 90% of the U.S. oil industry. Andrew Carnegie led the expansion of the steel industry, using new technology and ruthless cost-cutting to dominate steel production. Cornelius Vanderbilt made a fortune in railroads after earlier success in shipping. J. P. Morgan, a powerful banker, helped consolidate industries and had enormous influence over finance.

These industrialists often eliminated their competitors through aggressive tactics. They formed trusts and pools – agreements between companies – to control prices and markets. They also used vertical integration (controlling every step of production, from raw materials to distribution) and horizontal integration (buying out or driving out all competitors in the same industry) to create monopolies. With little government regulation initially, these giant companies could fix prices, lower wages, and influence politics. People observed that these elite white men had so much money that they could literally control government decisions.

Many politicians were friendly to business interests, and corruption was common – wealthy businessmen bribed lawmakers to ensure the government stayed “hands-off” (laissez-faire) and did not interfere with their growing power. This era saw extreme concentration of wealth: a few tycoons became multimillionaires while most workers remained poor. Critics nicknamed it the “Gilded Age” because beneath the glittering surface of prosperity were deeper problems of corruption and inequality.

Wealth Inequality and Social Darwinism

The rapid industrial growth created huge inequalities in wealth. The new class of millionaires lived in luxury, while factory workers and miners barely scraped by. By the 1890s, the richest 1% of Americans owned an astounding portion of the nation’s wealth, and big corporate trusts controlled entire sectors of the economy. This wealth gap led to significant class tension. Working people complained that a handful of “robber barons” were getting rich off the labor of the masses. At the same time, many among the wealthy elite believed that such inequality was natural and even beneficial. They adopted an ideology called Social Darwinism.

Social Darwinism applied Charles Darwin’s idea of “survival of the fittest” to human society. Social Darwinists argued that the strongest and most capable people (and companies) would naturally rise to the top, becoming rich, while those who were poor must be “less fit” or less capable. In their view, big corporations were successful because they were the “fittest”, and the government should not interfere with their dominance. This idea was used to oppose any regulation of business and to argue against helping the poor or the working class. It essentially told the rich that their wealth was proof of their superiority, and that helping the less fortunate (through laws or charity) would hinder natural progress. Social Darwinism provided a convenient justification for the laissez-faire(hands-off) policies of the time: if the poor were meant to be poor, then things like minimum wage laws or safety regulations were unnecessary.

Not everyone accepted these arguments. Labor activists and some reformers countered that extreme inequality threatened democracy and freedom. They pointed out that when a few have so much power, the majority are not truly free or equal. They also rejected the notion that workers were poor due to any personal failing; instead, they blamed low wages and an unjust system. Nonetheless, during this period, the ideology of Social Darwinism was influential among business leaders and politicians, reinforcing a lack of government action to address social problems. It would only be in the 20th century that more people began pushing the government to step in with reforms. But in the late 1800s, workers themselves took action collectively, leading to the rise of labor unions and organized resistance.

The Knights of Labor: A Broad Union Movement

As industrialization accelerated, workers sought ways to organize and fight for better conditions. The first major national labor union to emerge was the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, usually just called the Knights of Labor. The Knights of Labor was founded in 1869 by a group of Philadelphia garment cutters led by Uriah Stephens. Initially a secret society, it grew into a nationwide organization in the 1870s and 1880s. The Knights aimed to unite all types of workers into one big union – a very ambitious goal. Unlike later unions, the Knights of Labor welcomed almost every worker, including unskilled laborers, women, and Black workers (they only excluded a few groups like bankers, lawyers, and liquor dealers, whom they felt were not producers). This inclusive approach was remarkable for its time, since most other labor groups discriminated by race or skill and scared the elites who worried about the working class masses uniting against them and their interests. The Knights believed that by uniting all working people, they could change the system that oppressed workers.

The Knights of Labor had lofty ideals. They were not just fighting for higher pay; they wanted to reform the whole economic system. Their leaders spoke of creating a “cooperative commonwealth” where workers would own industries together, wealth would be distributed fairly, and all people would be respected for their labor. The Knights’ platform called for reforms like the eight-hour workday (instead of 10–12 hours), the end of child labor, equal pay for women, government ownership of railroads and telegraphs, and the establishment of worker-owned cooperatives. They also promoted education and solidarity among workers, setting up libraries and discussion groups. In essence, the Knights of Labor combined the roles of a union, an educational society, and a political movement.

By the mid-1880s, the Knights of Labor grew rapidly to become a potent force. In the wake of a severe economic depression in the 1870s (the Panic of 1873), many smaller trade unions collapsed, but the Knights survived and expanded. They won a major victory in 1885, when they led strikes against the railroad baron Jay Gould and successfully forced Gould to negotiate and restore wages on his railroad lines. This triumph over a powerful “robber baron” greatly boosted the union’s fame. Membership surged as workers across the country flocked to join. The Knights went from around 100,000 members in 1884 to hundreds of thousands by 1886. At their peak, they may have had 700,000 to 1 million members nationwide, including tens of thousands of women and Black workers (who in many cases formed their own local assemblies under the Knights’ umbrella). This made the Knights of Labor the largest labor organization in 19th-century America.

The Knights also showed political ambitions. They sometimes allied with radical movements and even formed labor parties in local elections. In 1886, some Knights backed Henry George, a famous reformer, for mayor of New York City, nearly propelling him to victory. That same year, unions and the Knights called for nationwide demonstrations on May 1, 1886, to demand the eight-hour day. This call led to a wave of strikes and rallies involving tens of thousands of workers across the country. The Knights of Labor appeared to be leading a new era of mass worker activism. However, 1886 would also prove to be the high point of the Knights – and the beginning of their decline – due to a tragic event in Chicago that shocked the nation.

The Haymarket Affair and Its Aftermath

In May 1886, labor demonstrations for the eight-hour day were occurring in many cities. In Chicago, on May 4, 1886, a rally was held at Haymarket Square to protest a violent incident from the day before (Chicago police had fired into a crowd of strikers at the McCormick Harvester plant, killing at least one worker). The Haymarket protest began peacefully with speeches despite rain. As police moved in to disperse the meeting, someone threw a bomb into the crowd of police. The bomb exploded, killing one officer instantly and mortally wounding six others. The panicked police responded with gunfire, shooting into the crowd of protesters. In the chaos, four civilians were killed and many more were injured. This event became known as the Haymarket Affair (or Haymarket Riot).

The Haymarket bombing had an immediate chilling effect on the labor movement. Although the bomb thrower was never identified, authorities and the press blamed anarchists and labor radicals for the violence, including the Knights of Labor though they had not organized the rally. Chicago police rounded up numerous known activists. Eventually, eight men (many of them immigrant labor organizers in the city) were put on trial for conspiracy to commit murder, even though there was little or no evidence linking them to the bomb (and several were not even present at Haymarket when it happened). The trial was highly controversial. All eight defendants were convicted; four were executed in 1887, one committed suicide, and the remaining three were later pardoned years later by the Illinois governor due to doubts about the fairness of the trial.

In the public mind, the Haymarket bombing connected labor unions with violence and radicalism. Newspapers portrayed the incident as the work of dangerous foreign-born anarchists intent on wreaking havoc. This led to a strong public backlash against labor organizations, especially against the Knights of Labor. The Knights were not actually responsible for the Haymarket bomb – in fact, their leader, Terence Powderly denounced violence. But the distinction was lost on many of the public. Many people, encouraged by sensationalist press coverage, began to see the entire labor movement as a hotbed of anarchists and bomb-throwers. Employers and government officials seized the opportunity to crack down on unions. In what has been called America’s first “Red Scare,” union members were painted as un-American radicals. As a result, the Knights of Labor’s reputation was badly damaged. Their momentum abruptly stopped.

After 1886, membership in the Knights of Labor plummeted. Many workers left the organization, and new people stopped joining out of fear or because of the anti-union atmosphere. The Knights, which had boomed so rapidly, fell into disarray due to internal conflicts and external pressure. By 1890 the Knights’ membership dwindled to around 100,000, and by the mid-1890s it fell to only 40,000. Essentially, the Haymarket Affair marked the end of the Knights of Labor as a leading force. The union limped on for a while, but had lost its influence. However, the ideas and energy that the Knights sparked did not disappear. Many former Knights members went on to form or join other labor groups (some joined socialist and populist political movements, others later became part of the Industrial Workers of the World in the early 20th century). Meanwhile, a different kind of labor organization was on the rise, one that promised a more pragmatic and cautious approach: the American Federation of Labor.

Immigration, Race, and Labor Exclusion

The late 19th century labor movement had to contend not only with hostile business owners and government forces, but also with divisions within the working class. Issues of immigration and race often divided workers, weakening their unity. During 1865–1900, the United States experienced large waves of immigration, especially from Europe (Ireland, Germany, and later Southern and Eastern Europe) and from Asia (particularly China). Immigrants were a major part of the industrial workforce, but native-born workers sometimes resented them. Many immigrants were willing to work for lower wages, and employers could use them as strikebreakers (workers who fill in for strikers), which bred resentment. Racial and ethnic prejudices deeply affected the labor movement.

Asian immigrants, especially Chinese workers in the West, faced the most extreme discrimination. White labor organizations on the West Coast argued that Chinese laborers took jobs and lowered wages. In the 1870s and 1880s, anti-Chinese hostility grew violent at times (for example, the Rock Springs massacre of Chinese miners in Wyoming in 1885). Even the Knights of Labor, despite their inclusive rhetoric, joined the crusade against Chinese immigration. The Knights officially supported the federal Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which was a law that banned Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States. The Knights as a national organization even refused to admit Chinese immigrants as members (although a few local Knight assemblies defied this and organized Chinese workers anyway). Some Knights of Labor assemblies and many other unions were also hostile to newer immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, though those groups did join the labor movement in significant numbers. Labor leaders like Samuel Gompers of the AFL were openly anti-Chinese; Gompers argued that Chinese workers, due to their low living costs, undercut American wage standards. This pressure contributed to the passage of Chinese Exclusion, the first U.S. law to bar a group of immigrants explicitly by ethnicity.

Black American workers also often suffered exclusion. After the end of Reconstruction in 1877, African Americans in the South were largely confined to low-paying agricultural and service jobs, or to sharecropping on farms despite having done most of the skilled tasks in the U.S. South while in bondage. When Black workers did enter industrial workforces (for instance, in southern railroad or iron industries, or moving north to cities like Chicago), they frequently found unions closed to them. Many craft unions (the core of the AFL) barred African Americans and women from membership. As a result, Black workers sometimes had to form separate unions or were used by employers as replacements during strikes, which fueled further racial tension. An important exception was the Knights of Labor: the Knights did welcome Black members, and by the 1880s they had tens of thousands of Black workers in their ranks. The Knights organized Black sugarcane laborers in Louisiana, for example, leading a strike in 1887 – though that strike was brutally suppressed by white militias. Overall, however, the mainstream labor movement of the Gilded Age did not prioritize racial equality. White unionists at times defended white job privileges and either ignored or actively supported the disenfranchisement of Black voters in the South (which weakened Black workers’ political power). This racial divide meant that the working class was not united against the industrialists – race could be used to pit workers against each other.

Likewise, women workers struggled for recognition. Women made up a growing part of the industrial workforce (especially in textile mills, garment factories, and food processing). They were typically paid far less than men and worked in similarly poor conditions. A few unions (including the Knights of Labor) organized women. The Knights actually hired a woman organizer, Leonora Barry, to travel and recruit working women. By the mid-1880s, the Knights had around 50,000 women members, which was groundbreaking at the time. Nonetheless, the idea of women in the labor force had little support from male unionists generally. The AFL, which rose after Haymarket, mostly ignored women workers, believing a man should earn a “family wage” to support his household while women ideally stayed home. As a result, women often had to agitate separately (for example, the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union formed in 1900, slightly later, to address women’s employment in clothing factories).

The government was more supportive of the racially and gender-exclusive AFL than of the Knights of Labor, because elites recognized that divisions of race, gender, and national origin could be used to weaken worker solidarity in a labor system already structured by exclusionary policies. Immigration and racial/ethnic/gender bias affected labor unity in this era. Employers frequently exploited these divisions. They would hire immigrant workers when native-born workers went on strike, or play Black and white workers against each other to break solidarity.

Divide and conquer was a common strategy: as one labor newspaper of the time observed, business owners would “exacerbate ethnic tensions in order to divide the workers”. The result was a segmented working class, with separate “tiers” of oppression. As historian Howard Zinn noted, the elites created a “terrace” of different levels of working people – “rewarding them differently by race, sex, national origin, and class, in such a way as to create separate levels of oppression”, which helped stabilize the pyramid of wealth by preventing a united challenge from below.

Despite these internal divides, the period from 1865 to 1900 saw the birth of a national labor movement. Workers organized unions, staged massive strikes, and even laid down their lives in conflicts like Haymarket and others, all in pursuit of a more just economic order. They did not topple the industrial giants of the Gilded Age, but they did succeed in bringing workers’ issues to the forefront of American consciousness. The struggles of this era – over hours, wages, safety, equality, and the rights of labor – set the stage for reforms in the decades to come. It was a time of enormous wealth for a few and hardship for many, and the clash between those forces defined the age. The legacy of labor resistance in industrial America during 1865–1900 can be seen as both the foundation of later labor rights and a vivid illustration of the deep tensions created by economic inequality in a rapidly changing nation.

References

- Brands, H. W. (2010). American colossus: The triumph of capitalism, 1865–1900. Anchor.

- Green, J. (2012). Crash Course U.S. History: The Industrial Economy [Video]. CrashCourse, YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=spOZJwWD2dc

- Licht, W. (1995). Industrializing America: The nineteenth century. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Nicholson, P. Y. (2004). Labor’s story in the United States. Temple University Press.

- Parfitt, S. (2016). The rise and fall of the Knights of Labor. History Today, 66(11), 45–52.

- Zinn, H. (2005). A people’s history of the United States. Harper Perennial Modern Classics.